Sinofuturism: China, Orientalism, and the Path Forward

10-minute read

Narratives about the rise of China have become fairly common in news media. But they might have more to tell about ourselves than what is happening at the other end of the world.

After European Futurism’s infamous, deadly flirtations with the vices and virtues of speed, the flights of Afrofuturist emancipatory science fiction from Eurocentric narratives and the reactionary aesthetics of Gulf futurism, 28 years after the end of history has been proclaimed, a newly outrageous force seems to emerge from where the sun rises. To be sure, the media has for a long time been eager to document signs of the Sleeping Giant’s awakening: it seems like every year finally sees the emergence of a Chinese global hegemony.

Now, as the British Empire and the United States have taught us, every ‘proper’ world superpower needs more than simply obvious indicators of material success. The rest of the world needs to be dragged under symbols of national exceptionalism, in the same way as western movies have established the ascendancy of American culture by smuggling images of honest, hard-working freedom seekers into the collective imaginary. The most common positive stereotype about Chineseness today is the attainment of superhuman self-mastery through diligent training; Quentin Tarantino’s cinematography, which owes a lot to Chinese (and Japanese) productions, notably in the case of his Kill Bill movies, portrays these themes in a uniquely kicky fashion. Such self-dedication lays the foundation for the achievement of larger projects that could not have been achieved without the help of others, which is, incidentally, where we find the fundamental blueprint of all communist praxis.

If worldwide recognition is downstream from soft power, then, despite a number of hiccoughs, China rows steadily towards it. No matter how many grey areas tarnish the plausibility of China’s goodwill when it comes to joining the world community, such as allegations of human rights violations (reports of extant concentration camps known as laogai) and the political tensions with its neighbours (notably Tibet and the Taiwan question), the country continues to enjoy an essential and increasingly reputable role in the world market. Who ever said that globalisation rhymed with democracy?

In fact, China’s most effective PR is precisely to remain insular and further cultivate its will to remain cut off from Western cultural influence. Its own perceived exoticism serves as a currency that cannot be overlooked from a geopolitical point of view. The Great Firewall of China, to use a singular example, blocks access to most Western companies online: Facebook, Twitter, Wikipedia, Android, and most Western news outlets can only be accessed by using a VPN – one may as well draw up a list of sites that are not blocked in China, but the trouble is that those are always changing. This expansive censorship fuelled the need for Chinese virtual equivalents to come in and replace them. As it is a truth universally acknowledged that money has no smell, however, Western banking sites manage to get a pass in what has recently become the world’s second largest Foreign Direct Investment recipient (after the United States and before Hong Kong). So much for a nominally communist state.

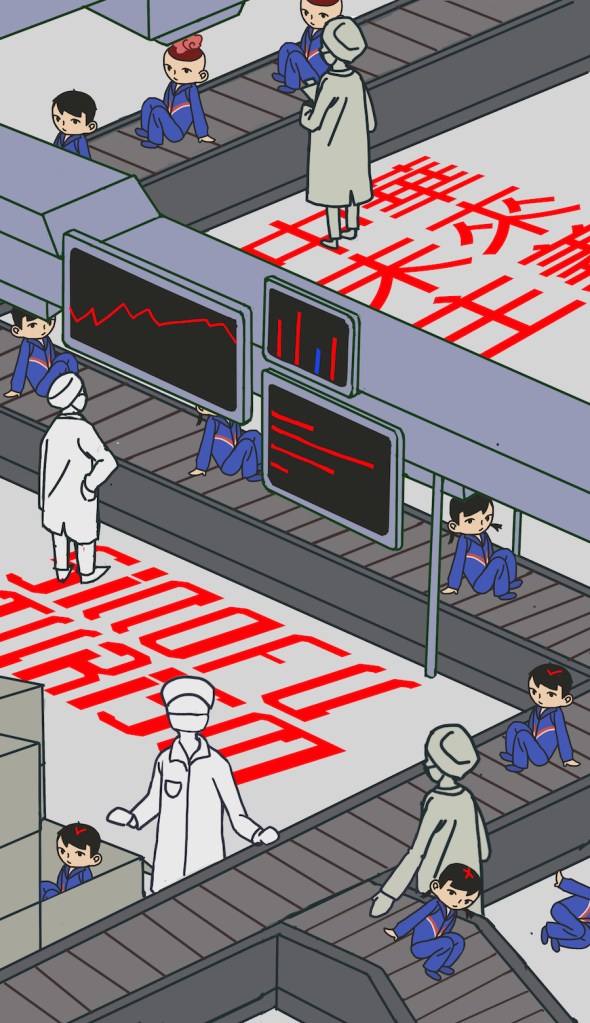

China has routinely served as a setting for Western projective tendencies that still persist today. Our democratic system may have its flaws, but at least we’re not China! The country’s supposed adoption of a curious blend of communism and capitalism did not fail to perpetuate a certain idea of Otherness in the form of an outlandish, oxymoronic system. In 2016, Lawrence Lek, an artist of Chinese-Malaysian decent born in Germany and based in London, produced an hour-long essay film entitled “Sinofuturism (1839-2046 AD)” which playfully draws a satire of widespread representations of China. The footage contains multiple collages of 3D-modelled futuristic, Blade-Runneresque urbanscapes and news footage of contemporary China among others, along with a feminine speech synthesis reciter impassively telling us what Sinofuturism is all about.

Lek takes the dates 1839, the beginning of the Opium Wars which are often considered to mark the onset of the Century of humiliation by Western powers, and 2046, a reference to Wong-Kar Wai’s film of the same name. These dates were chosen to encompass the nineteenth century industrial revolution that China was practically force-fed, as well as the incoming fourth industrial revolution, which would, according to Lek, start from China’s full-on adoption of industrial automation and AI technology, thus espousing a model that would in turn extend to a planetary scale.

The story goes like this: Sinofuturism is “a movement not based on individuals, but on multiple overlapping flows […] of populations, of products, and of processes,” which presents itself as “a science fiction that already exists.” The rationale here is that there is indeed, in a very real sense, a ubiquitous aspect to China, one that is found in our everyday lives in the form of “a spectre already embedded into a trillion industrial products, a billion individuals, and a million veiled narratives.” So far, so good. But the most daring of Lek’s claims is probably that Sinofuturism is “in fact, a form of artificial intelligence, a massively distributed neural network, focused on copying rather than originality, addicted to learning of massive amounts of raw data rather than philosophical critique or morality, with a post-human capacity for work and an unprecedented sense of collective will to power.” If art is to be conceived of as a realm of provocation, then we surely are right in the middle of it.

The film takes on seven stereotypes of Chinese culture, namely computing, copying, gaming, studying, addiction, labour, and gambling. If there is a part of truth in every stereotype, as Lek himself believes, merely dismissing them would be injudicious. Rather than attempting to debunk these clichés, Lek takes them up as “guiding principles” of a movement that reveals a disturbing gap between the human and AI, “conventional understanding” and “the mystique of unconsciousness,” following the binary described by Edward Said in his concept of Orientalism. Once again, Lek questions our usage of this latter concept which has come to be used as “a generalised swear word” that simplifies human relations as much as the very cultural depictions that Orientalism identifies.

All in all, Lek’s work suggests that ascribing moral attributes to collective bodies may not constitute a truthful vision of the world, but at least it provides narratives whose critical assessment helps us navigate a world that runs on arbitrary meaning. Lek confessed that Sinofuturism “is not a manifesto. It is a conspiracy theory.” The film’s bleak atmosphere, its cold factuality and looming subversion play on fears of an imminent (western) world invasion by inhuman (eastern) forces, deeply inconsiderate of dusty fetishisms of preservation. The project can be summed up in two ways: on the one hand, it lampoons superficial accounts of artistic, avant-garde projects such as this one by popcorn media thriving off the very pointing of fingers to convenient bogeymen, and, on the other hand, it offers a new way of understanding our fears and fascination for the unknown.

We are told and indeed tell ourselves countless conspiracy theories all the time so that we can make sense of things. We are all somewhat guilty of lazily leaping to conclusions, relying on kneejerk judgements, othering people and things we do not care to better understand. All good art is meant to make us question our ways of thinking about a world whose entropy, the ultimate scientific conspiracy theory, eats away at everything we once thought would last forever. In an interview, Lek mentions the idea that Sinofuturism precisely points toward Chinese passivity, yet another stereotype, as an ultimate means of survival, one that, we might surmise, can indeed resort to defensive scare tactics. Unlike Western exhortations to stick out from the crowd, the shadow of authoritarian dynasties all the way down to Maoism lingers on in Chinese society, making venturous originality in its domestic art a rare sight.

Things are nevertheless bound to change as China makes its way into a globalised modernity and finds its own enlightened path towards the future. The scripts are already encoded, patches from all around the world are being applied, the program only awaits activation. But that is a story that has yet to unfold to finally complete China’s seemingly eternal return.

Leave a comment