Translating Gatsby

In collaboration with Roxane Gindre.

All published translations are equal, one may say,

but some translations are more equal than others.

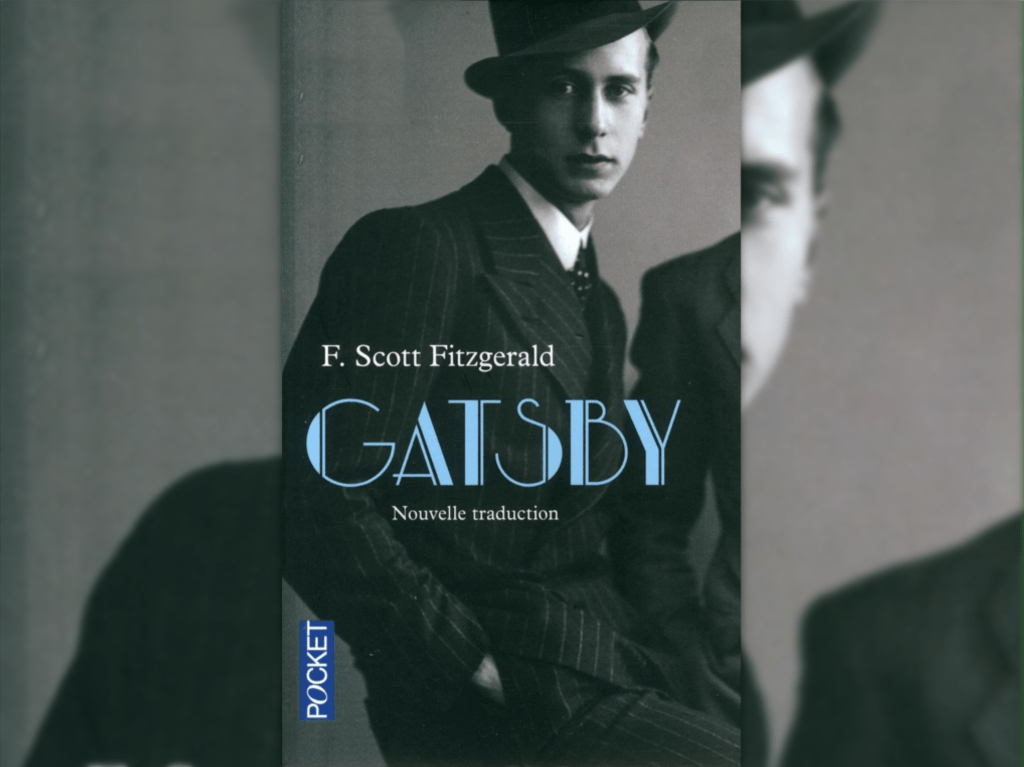

Some years ago, I was presented with a series of sentences which were supposed to be some of the most difficult clauses of English-speaking literature to translate into French. Among them was the Sisyphean last sentence of The Great Gatsby which goes as follows: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” The summer of that same year, a friend of mine randomly stumbled across a “nouvelle traduction” of Fitzgerald’s novel. We immediately felt the counter-intuitive urge to open the book backwards.

The translation was by Jean-François Merle and was published in 2013. After reading the last sentence once, we found its effect rather convincing, but the more we read it, the more it looked close to perfect to our widening eyes. It goes like this:

C’est ainsi que nous avançons, esquifs luttant contre le courant, refoulés dans le passé, sans cesse.

(So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.)

If you did read it thrice as I recommend you to, you were probably struck as we were back then by the “ceaselessly” sent at the very end of the sentence. Not only does this shift allow the novel to end on the idea of endless and meaningless repetition, it also deepens the struggling meaning of the original sentence. The perpetual backwash can be linked only to its adjacent bit, but it can also be applied to the three previous parts of the sentence. Even if the ternary rhythm of the original sentence is broken, this lonely post-comma “sans cesse” brings the final touch and encapsulates the idea of the whole sentence within two words.

The progressively shortening segments (five words, five words, four words, two words) bring a closing rhythm to this sentence, allowing it to end the book rather unabruptly. Paradoxically, this sentence is expressing the never-ending feature of a struggle with a very smooth rhythm. The other paradox and the beauty of Fitzgerald’s sentence also come with the idea of going forward (“beat on”) into your past and not into your future. This phrasal verb was efficiently translated into two bits (“avançons … luttant”) avoiding a loss of meaning (other translators kept only the struggle aspect as in “nous luttons” in 2009 or “nous nous débattons” in 2012).

You could, of course, see in this last sentence the circularity many books are praised for. But let us remember that Gatsby is dead and buried. This last sentence breaks away from the novel and its temporality, it is no longer tethered to a particular time and place. The narrator gets somewhat trapped into a temporal loop, he is not living his memories again, he is simply drifting there, endlessly. What is more, after a whole book narrated by a first-person narrator, the tone shifts to an almost philosophical voice using an impersonal “we,” hence the présent de vérité générale. This final sentence is uttered almost out of the story.

The translation expresses the upside-down time through a reversal of the usual past-present-future scheme. It starts with the idea of future, of going somewhere (“C’est ainsi que nous avançons”), and ends with the idea of past and accomplishment (“refoulés dans le passé”) both surrounding the present moment and its struggle (“esquifs luttant contre le courant”). This is finally expressed in the very well-chosen tenses linked to these ideas : the participe passé for the idea of past in “refoulés,” the participe présent for the continuous present of “luttant” and finally the idea of future turned paradoxically into the present tense “avançons.” It seems that we will never manage to move on, that we will never leave this boat as we are doomed to repeat this very meaningless action again and again. And Sisyphus goes on, lurking over East Egg.

Leave a comment